The 1924 Cross Burning at Columbia

The 1924 Cross Burning at Columbia University [1]

After midnight, on April 3, 1924, several automobiles drove onto the Columbia campus at 116th Street. Twenty or so men, cloaked in the white hoods and robes of the Ku Klux Klan, stepped out of the cars and carried a seven-foot-tall wooden cross down onto the grassy lawn known as South Field. They dowsed it with kerosene and set it on fire. The flames of the burning cross could be seen from all the residence halls on the quad, as well as from the windows of neighboring apartments.[2]

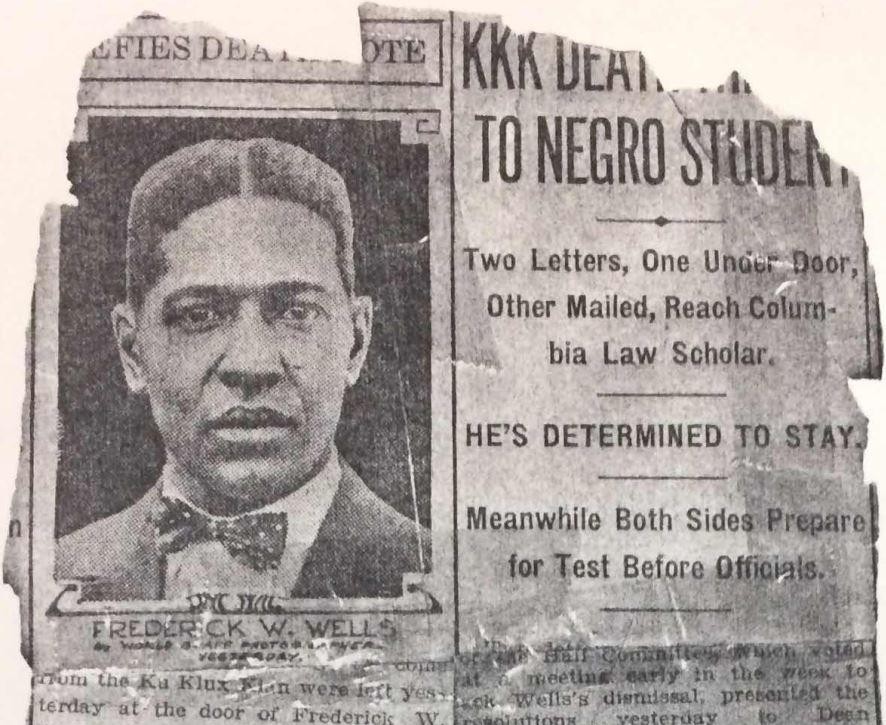

This was an act of white-supremacist terrorism. Its target was Frederick W. Wells, a Black law student who had recently moved into a room in Furnald Hall. While the cross burned outside, white students ran through the corridors of the residence building, screaming “down with the Negro,” and “Put the N----- out!”[3] Wells barricaded his door, preparing to defend himself and ready to “show his teeth” in case of assault.[4] When he awoke the next morning – after a fitful sleep – he found that a threatening letter, signed by the Ku Klux Klan, had been slipped under his door during the night.[5]

Frederick Wells

Originally from Tennessee, Wells was 25 years old in the spring of 1924.[6] Already an accomplished student when he arrived at Columbia Law School, he had attended Wilberforce University and Ohio State, before winning a YMCA scholarship to pursue graduate work at Yale.[7] In addition to his schooling, Wells participated in several civic organizations in Harlem. He belonged to the Charles Young Foreign Legion Post and was a member of the Eta chapter of Alpha Phi Alpha, a Black fraternity.[8] He had impressed friends and associates with his intelligence and determination, and was “well known among the younger set in this city.”[9]

Highly regarded in Harlem, Wells spent his first weeks on Columbia’s campus in comparative anonymity. On March 5th, he moved into room 528 in Furnald Hall.[10] Perhaps anticipating trouble, he never invited visitors, kept to himself, and focused on his work. His neighbors on the corridor found him to be perfectly respectable. “Quiet and gentlemanly in his manner, correct and serious and clean in his person,” he maintained the character of “a serious and purposeful student.”[11]

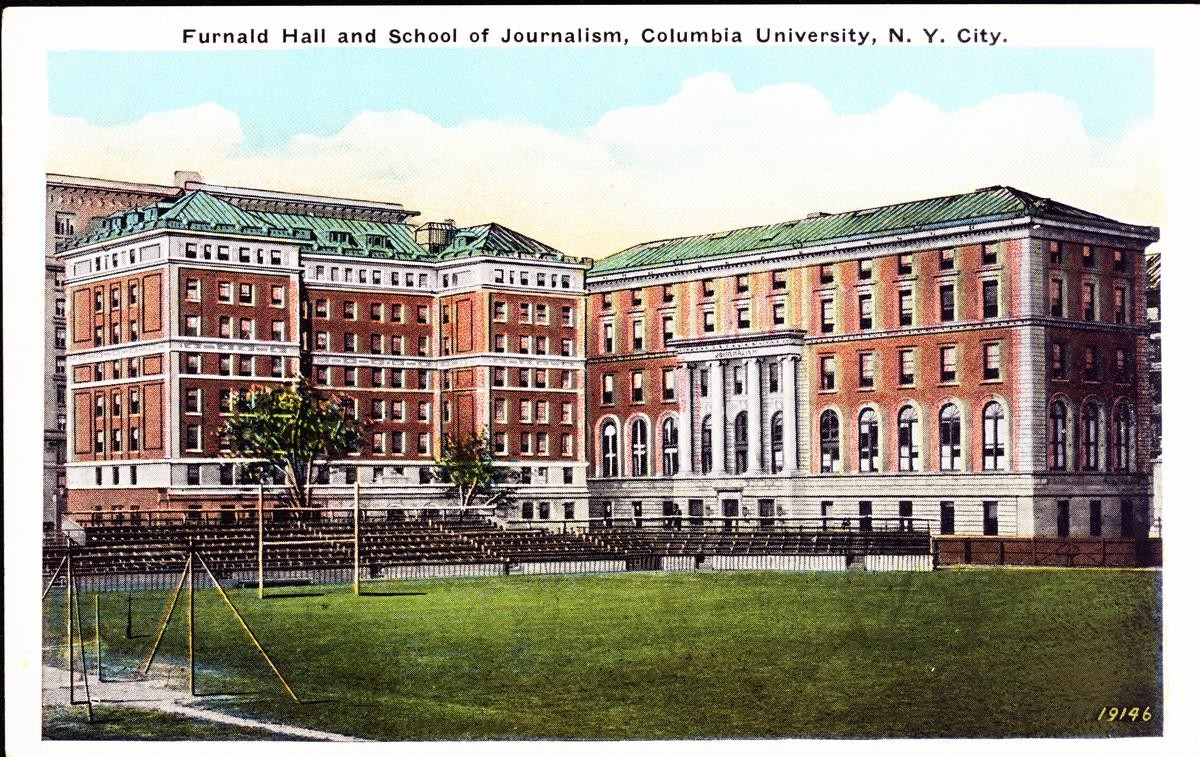

Furnald Hall

Furnald Hall already had a reputation as a site of race hatred and “bad feeling.”[12] Home to university graduate students, its population included one or two Asian residents,[13] but the vast majority were white, with about 15 percent coming from the American South.[14] A Black elevator operator in the building had recently complained of prejudicial treatment.[15] It’s possible that Wells intentionally maintained a low profile and avoided any sign of trouble. White residents at first thought Wells, too, was a delivery boy, a porter, or an elevator operator.[16] But, when several Southern students eventually did identify him as a resident, they moved quickly to create an outraged “ferment” over his presence. At the beginning of April, a small but organized group of angry students demanded that he be asked to leave: “for the peace of all concerned.”[17]

The White Supremacists Who Sparked the Terrorist Act

A white law student from North Carolina named John B. Rucker led the efforts to expel Wells from Furnald. Described as a “trouble maker” and a “disagreeable fellow,”[18] Rucker aggressively advocated for the separation of races.[19] Though he denied being a member of the Ku Klux Klan, his opposition to integration even made headlines in his hometown newspaper, which commented on his feelings against “placing all races and colors in the same dormitories.”[20]

A few days before the cross burning, Rucker had urged Herbert Hawkes, the dean in charge of campus residence halls, to expel Wells from the residence hall. When Hawkes supported Wells’ right to keep his room, Rucker offered a dark warning: “Well, I will give you some publicity,” the dean recalled him saying, “and see how you like that.”[21]

Hoping to stir outrage in the press, Rucker told his story to newspaper reporters around the city. Articles appeared in the World, the American, the Herald, and even the Washington Post, which each printed articles about the campus controversy on April 2nd – the day before the cross burning. Administrators certainly opposed having university affairs exposed in such a public way; but whatever Rucker’s expectations may have been, the coverage tended to be sympathetic toward Wells, and praiseful of dean Hawkes’ determination to stand by him.

Columbia Deflects

Herbert I. Hawkes, 1929

Herbert I. Hawkes, 1929

In his defense of Columbia, dean Hawkes presented an ideal – and misleading – picture of racial tolerance on campus. “There have always been Negroes at Columbia,” he insisted to reporters, “as well as students of other nationalities, and no discrimination is countenanced against any.”[22] Claiming a lack of records, the administration could not provide accurate data about the number of Black students at the university, estimating that there were six Black students in the college and “probably an equal number” in the various graduate programs.”[23]

Wells, and others, noted throughout the controversy, that the documentation for residence hall accommodations did not require the applicant to list his race on the submission form. In theory, they were race-blind. Though no formal policy of segregation existed, students other than Wells – including Langston Hughes – had encountered de facto racism in the dormitories.[24] Southern clubs, blackface humor, and minstrelsy dominated campus culture.[25] Rumors held that a student branch of the Ku Klux Klan operated in secret, and at the 1923 commencement exercises, those rumors appeared to be confirmed when uniformed members of the KKK had paraded “in broad daylight, with the blistering sun overhead and no attempt at secrecy.”[26]

The Aftermath & Wells's Response

Few physical traces remained on the morning after the attack. “Only a blackened spot, just north of the baseball diamond, marked the place where the cross was set afire,” newspapers reported the next day.[27] But the story had become a national sensation, the university was on edge, and there existed “a general state of intense interest in the whole matter by the public in general.”[28]

All eyes turned to Wells. And he resolved to stand firm. “I came here to get an education and went through the customary procedure in obtaining my room,” he told a reporter with the New York Times. “I shall remain in it as long as I have the money to pay for it. That is final. I will not be bullied in any way.”[29] Although a second threatening letter arrived for him in the mail that day, Wells’ determination was strengthened by an outpouring of encouragement from the Black community. James Weldon Johnson, secretary of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, sent him a telegram of support, which was widely published:

I wish to express the admiration which the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People feels for the manly stand which you have taken in the matter of the protest against your presence as a resident in Furnald Hall Columbia University. We feel that you appreciate that in this case you are not merely an individual, but you are representing the hopes and aims of the best and bravest in the Negro race today. We realize and understand that the position in which you find yourself may incur some embarrassment for you, and even some personal inconveniences but we feel confident that you are willing and determined to withstand them for the sake of the principle at stake. I also wish to assure you that this association and its national office stand ready to assist you in this fight in every way possible and to give you its fullest support.[30]

While allies hurried to support Wells, John Rucker found himself on the defensive. Several members resigned from the Furnald Hall building committee, accusing Rucker of having misrepresented the feelings of the majority of residents. Despite Rucker’s previous exertions to have Wells expelled, he now claimed only to have been serving at others’ behest. When one student reported that he had seen Rucker among the hooded figures on South Field, a panicked Rucker denied any knowledge of, or adherence to, the Ku Klux Klan.[31]

Columbia Responds

Columbia’s leaders took the cross-burning seriously enough to have three detectives of the New York Police Department Bomb Squad stationed at Furnald Hall. And dean Hawkes wrote a letter to Wells’ father assuring him that “safety precautions were being taken to protect his son.”[32]

Publicly, however, the administration’s foremost priority was to move on from the incident as quickly as possible. No formal investigation appears to have been attempted to discover the identity of the hooded men. Vague rumors swirled that the perpetrators had come from a Klan chapter in Montclair, New Jersey.[33] Discussion of the cross burning quickly abated; even the Columbia Spectator stopped covering it on the day after the attack. “I have talked with several students supposed to have witnessed the burning of the cross,” Hawkes said. “I feel sure it was done by non-students.”[34] Moving on was goal number one. “I hope that the whole matter will blow over in the course of a day or two and that the University will not be injured by the incident,” Hawkes wrote to Annie Nathan Meyer, an important institutional benefactor.[35]

Wells Transfers to Cornell

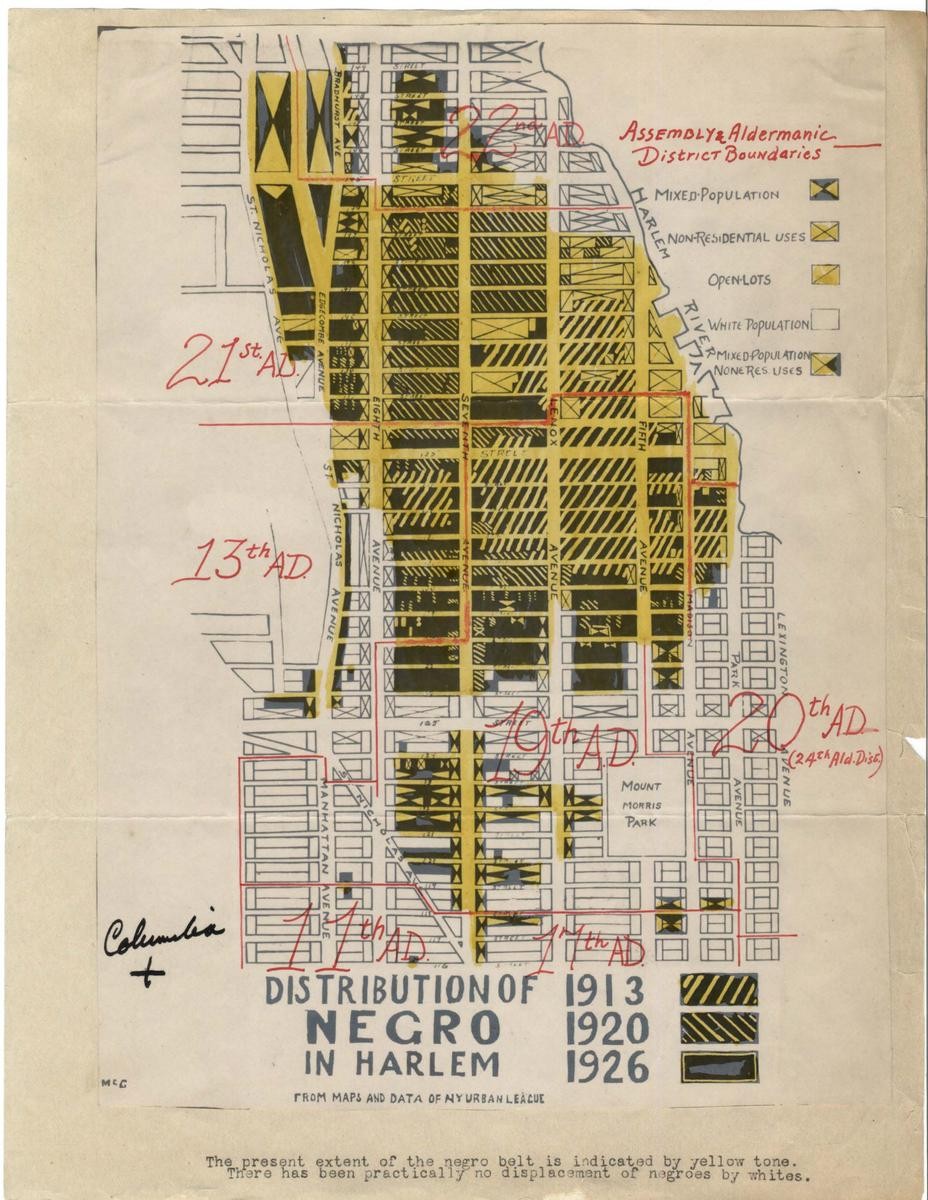

Distribution of Negro in Harlem 1913, 1920, 1926 from Maps & Data of NY Urban League

Distribution of Negro in Harlem 1913, 1920, 1926 from Maps & Data of NY Urban League

Wells finished out the term in the residence hall. Although he had already paid for summer accommodations in Hartley Hall – and had reserved his room in Furnald for the following year – he did not return to Columbia Law School. Instead, he left the university to complete his law studies at Cornell.[36] Wells’ dramatic encounter with residential segregation appears to have influenced the rest of his career. In Los Angeles, and then in New York City, he would spend decades working to improve living conditions for disadvantaged people. His efforts led to several model housing developments in Harlem and the Bronx. Frederick W. Wells died in 1979.[37]

Although Wells’ courage and the university administration’s defense of equal opportunity received praise at the time as a victory for civil rights, the long-term outcome resulted in a decline of equity. The cross burners may not have succeeded in terrorizing Frederick Wells, but they did accomplish their goal of impacting university policies.

Columbia Residence Halls Respond by Institutionalizing Racism

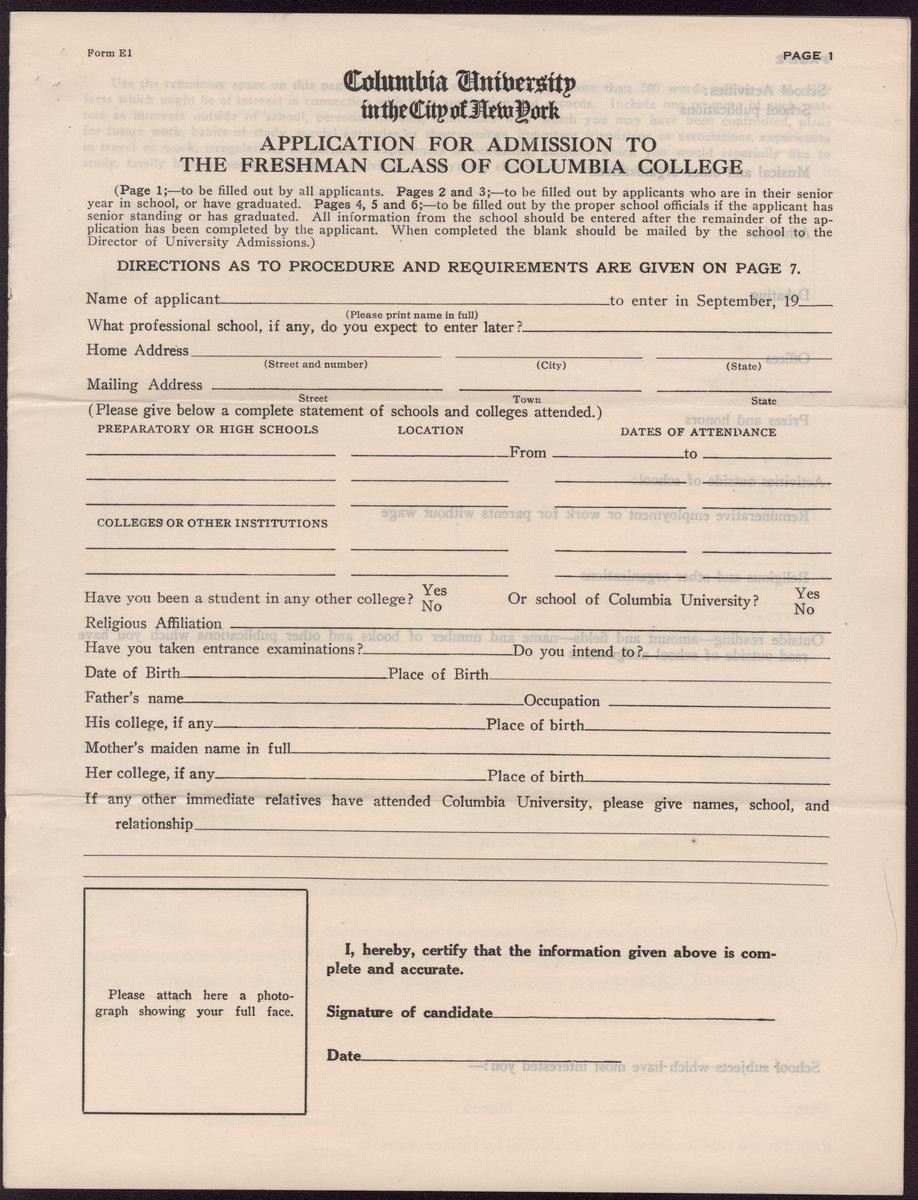

1932 Columbia College Application

1932 Columbia College Application

Beginning in the summer of 1925, a few months after the cross burning, Columbia’s residence hall submission forms – for the first time – included a space for applicants to list their race. This line in the application was accompanied by an explanation that this information was required “in order to assist in congenial grouping in the halls.”[38] The administration’s language – “congenial grouping in the halls” – was distressingly similar to the words Rucker and his racist followers had used, when they asked for Wells to be removed “for the peace of all concerned.”

As Black students at the time noted, this represented a major step backward in race relations at Columbia University.

*****

[1] This summary draws on the research of Trey Greenough and Thomas Germain. For a full account see: Germain, “Bright Spots Giving Sign in A Dark Sky” - The Columbia University Cross Burning of 1924.”

[2] “Columbia Residents Did Not Burn Cross, Authorities Believe,” Columbia Spectator (April 4, 1924). Conflicting testimony exists for all of these details. The estimated number of participants in this attack range from about twelve to more than twenty. Some sources suggest that the men did not wear Klan robes, but were in “civilian dress.” According to some accounts, the cross was about six-feet high.

[3] “Klan Burns Fiery Cross on Campus of Columbia,” Philadelphia Tribune (April 12, 1924); “Cross-Burning Stirs Columbia Student Body,” Baltimore Sun (April 4, 1924).

[4] “Cross-Burning Stirs Columbia Student Body,” Baltimore Sun (April 4, 1924).

[5] “Columbia Residents Did Not Burn Cross, Authorities Believe,” Columbia Spectator (April 4, 1924); “Death Threat Sent to Columbia Negro,” New York Times (April 5, 1924).

[6] Census records for Wells are contradictory. But contemporary newspaper accounts – many of which were based on personal interviews with Wells – almost all give his age as 25.

[7] “Flaming Cross Set on Columbia Campus,” New York Evening Post (April, 3 1924).

[8] “Fiery Cross Brings Columbia Negro Aid,” New York Times (April 4, 1924).

[9] “Wells Sees Cross Burn; Defies Klan,” The Pittsburgh Courier (April 12, 1924).

[10] Wells had come to campus for the spring term; he had been waitlisted for a residence hall room, and had moved into his accommodations midway through the semester.

[11] “Columbia Whites in Arms Against Colored Student,” Philadelphia Tribune (April 5, 1924).

[12] For more on racist attitudes and discrimination faced by students of color on Columbia campus, see: T.M. Song, “Scholars on the Margin: Global Intellectual History of Anthropologists and Educationists of Color Trained at Columbia University, 1897-1937,” History Department Senior Thesis, 2020. https://history.columbia.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/20/2020/05/Song-Tommy_SNR-Thesis_web.pdf

[13] “Call on Columbia to Dislodge Negro at Furnald Hall,” New York Evening World (April 2, 1924).

[14] “Death Threat Sent to Columbia Negro,” New York Times (April 5, 1924).

[15] “Call on Columbia to Dislodge Negro at Furnald Hall,” New York Evening World (April 2, 1924).

[16] “Columbia Says Black Student Must Stay,” Afro-American (April 4, 1924); “Furnald Residents Object to Negro Living in Dorm,” Columbia Spectator (April 2, 1924); “Fiery Cross Brings Columbia Negro Aid,” New York Times (April 4, 1924).

[17] “Call on Columbia to Dislodge Negro at Furnald Hall,” New York Evening World (April 2, 1924).

[18] Walter White, “Memorandum in re: Interview of Assistant Secretary with Dean Hawkes of Columbia University” (April 2, 1924). Papers of the NAACP, Part 03: The Campaign for Educational Equality, Series A: Legal Department and Central Office Records, 1913-1940. ProQuest History Vault.

[19] Although Rucker led the early efforts to oust Wells, once public opinion rallied to Wells’ defense, Rucker attempted to distance himself from his prior stance. His friends denied to the Spectator that Rucker had played an active role, see: “Furnald Committee Defends Chairman,” Columbia Spectator (April 7, 1924).

[20] “J.B. Rucker Gets Law License in NY,” Undated Newspaper Clipping, Wake Forest University Special Collections & Archives. https://wakespace.lib.wfu.edu/handle/10339/58803

[21] Walter White, “Memorandum in re: Interview of Assistant Secretary with Dean Hawkes of Columbia University” (April 2, 1924). Papers of the NAACP, Part 03: The Campaign for Educational Equality, Series A: Legal Department and Central Office Records, 1913-1940. ProQuest History Vault.

[22] “Fiery Cross at Night Points to Protest Against Negro,” Columbia Spectator (April 3, 1924).

[23] “Columbia for Equal Rights,” Boston Globe (April 3, 1924).

[24] T.M. Song, “Scholars on the Margin: Global Intellectual History of Anthropologists and Educationists of Color Trained at Columbia University, 1897-1937,” Senior Thesis, Department of History, Columbia University (2020): 2.

[25] Song, “Scholars on the Margin,” 12.

[26] “‘Klan’ Parade Thrills Visitors at Columbia,” New York Tribune (June 7, 1923).

[27] “Cross-Burning Stirs Columbia Student Body,” Baltimore Sun (April 4, 1924).

[28] “Wells Sees Cross Burn; Defies Klan,” The Pittsburgh Courier (April 12, 1924).

[29] “Negro at Columbia Defies his Critics,” New York Times (April 3, 1924).

[30] Telegram from James Weldon Johnson to Frederick W. Wells, April 3, 1924. Papers of the NAACP, Part 03: The Campaign for Educational Equality, Series A: Legal Department and Central Office Records, 1913-1940. ProQuest History Vault.

[31] “Wells Sees Cross Burn; Defies Klan,” The Pittsburgh Courier (April 12, 1924).

[32] “Frederick W. Wells Papers Finding Aid,” Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture; https://archives.nypl.org/scm/20602#descriptive_identity.

[33] “Wells Sees Cross Burn; Defies Klan,” The Pittsburgh Courier (April 12, 1924).

[34] “Cross-Burning Stirs Columbia Student Body,” The Sun (April 4, 1924).

[35] Herbert Hawkes to Annie Nathan Meyer, April 7, 1924. Papers of the NAACP, Part 03: The Campaign for Educational Equality, Series A: Legal Department and Central Office Records, 1913-1940. ProQuest History Vault.

[36] “Columbia for Equal Rights,” Boston Globe (April 3, 1924).

[37] “Frederick W. Wells Papers Finding Aid,” Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture; https://archives.nypl.org/scm/20602#descriptive_identity.

[38] “Columbia University Begins Dormitory Segregation,” Baltimore Afro-American (August 29, 1925).