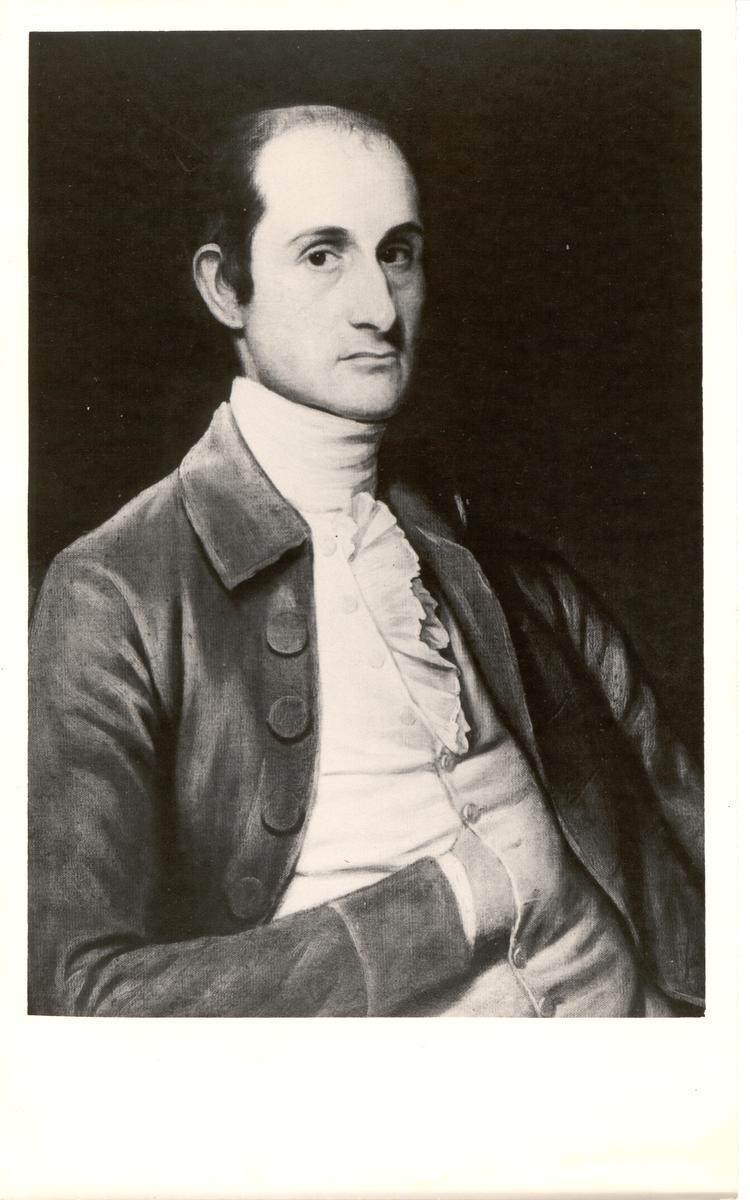

John Jay

A firm believer in the immorality of slavery and a supporter of gradual emancipation, John Jay (1745-1829) still enslaved people for most of his life. While Jay consistently criticized slavery, he carefully weighed its immorality against any impositions on white people. In his own case, Jay proved willing to enslave people to ensure his financial interests and, in his mind at least, to protect their well-being. As long as enslavement ended in freedom, Jay considered his ownership of humans broadly acceptable. More a reformer than a radical, Jay stood at the vanguard of white antislavery politics in New York, working consistently to help build support for ending slavery.

Early Life

Born to a slaveholding family in 1745, Jay grew up on an estate outside of New York City where roughly a dozen enslaved people were forced to care for and enrich his family. Long before his birth, Jay’s father and grandfather had invested in a variety of mercantile ventures, including importing more than a hundred enslaved people to New York from the Caribbean. As a young man, Jay was cared for by an enslaved man named Claas.

In 1774, Jay married Sarah Livingston, a member of one of colonial New York’s richest families. Although her father was a lawyer, Livingston’s extended family included numerous merchants who also imported enslaved people to the United States. At the time of her marriage, Sarah Livingston enslaved at least one woman, Abigail, who later attempted to flee from the Jay’s in France.

Post Revolutionary Era

As early as 1777, John Jay supported a ban on slavery in New York even as his family continued to rely heavily on enslaved labor. In 1779, Jay purchased an enslaved man, Benoit, for himself. Five years later, Jay drafted a plan for Benoit’s eventual manumission. Even as Jay claimed that “the children of men are by nature equally free and cannot without injustice be either reduced to or held in slavery,” Jay refused to free Benoit until he had earned “a moderate compensation for the money expended on him.”[1]

As the United States floundered after the American Revolution, Jay worked to bolster the government, arguing for a stronger, centralized state. Like many of his northern peers, Jay prioritized the preservation of the Union over almost every other consideration. As a result, he accepted numerous compromises, including some that helped protect slavery. As it became clear that a national ban on slavery was unlikely, Jay refocused his attention on New York.

Political Career & Jay's Hypocrisy

In 1785, John Jay helped found the New York Manumission Society, an early anti-slavery organization. With Jay as president, the group proclaimed: “It is our Duty, therefore, both as free Citizens and Christians… to endeavour, by lawful ways and means, to enable [enslaved people] to Share, equally with us, in that civil and religious Liberty… which these, our Brethren, are by nature, as much entitled as ourselves.”[2] At the while, the organization allowed its members to own other humans.

While serving as Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court during the 1790s, Jay continued to enslave five people. As he later argued in his own defense, he purchased enslaved people and manumitted them after “their faithful services...afforded a reasonable retribution.”[3]

During his first gubernatorial campaign in 1792, Jay’s adversaries depicted him as an abolitionist, contributing to his narrow defeat. Rejecting the claim, Jay rearticulated his longstanding support for gradual emancipation while still noting that all people had a “natural right to freedom.” A savvy politician, when Jay became governor in 1795, he largely avoided the topic of slavery. Behind the scenes, however, he supported a new effort to end slavery in the state. Pushed by the New York Manumission Society and the state’s black population, New York passed a gradual emancipation bill in 1799 although slavery remained legal until 1827.

In 1801, Jay retired to a country home in Bedford. Although slavery was still legal, the emancipation bill contributed to the institution’s steady decline. This held true for the Jays as well. In 1800, Jay enslaved five people. Ten years later, he only owned one person. In the end, John Jay lived to see slavery finally outlawed in New York, dying in 1829.